sentry hill & mr punch

several photographs by william fee mckinney feature a miss annie baird. one photograph features her in 1902 in a large group at a social function at sentry hill, then two much later photographs feature her sat upon a chair in front of a doorway at sentry hill, posed with a copy of the satirical british magazine punch in her hands, one looking at the camera with the magazine on her lap, in the other she looks at the magazine.

we can likely date these two later photographs to sometime around 1912-17- as the sitter’s wedding or engagement ring is visible, and her wedding date was 2 january 1914. further visual research may be able to indicate the exact date of the magazine, which features very much as a prop within one of these two photographs, as a representation of a literate woman on an ornate dining chair at the doorway of a subtantial home, looking over an issue of one of the most influential, and characteristic, british magazines of the era.

there is some contrast across this 1912-17 period in how political affairs from ulster or ireland are featured or characterised visually in cartoons or reports in punch magazine. across the first half of ww1, 1914-16, when the events of the war had become by far the predominant subject material, there are very few cartoons on political affairs from ulster or ireland. this is in stark contrast to the period just before the war – by 1914 across the period of the home-rule crisis, the ulster volunteer force, larne gun-running and the ulster covenant, the magazine was running half of its cartoons on irish political themes (i). and of course, in the period immediately after the easter rising affairs from ulster or ireland are prominently featured.

some examples from the issues of punch from 1916 in the months before the easter rising: small cartoons on irish figures feature within the magazine’s house of commons political sketch ‘essence of parliament’ column of 5 april 1916, with carson characterised as a skilled and shrewd political operator, indeed within the common stereotype (of him) as of the stern, unyielding Ulsterman (ii) featured in the magazine in this period,

and in issues from 26 january 26th and some weeks earlier on 12 january 26th the same ‘essence of parliament’ columns had featured respectively the cartoons “i’ll not have conscription” which featured carson characterised as shrewd and forceful, while john redmond is featured in the magazine’s characteristic register for him through a demeaning caricature as a rather buffoonish figure, as either hopelessly unprofessional or a self-important fool or positively ridiculous (iii), or even as a stupid, bloated and feckless gombeen man, often with a pig in tow (iv)

and although punch magazine at this time was no longer featuring what had been its common victorian era cartoon portrayals of the irish as simian-like brutes, nonetheless in this later period english cartoonists were losing their appetite for simianised paddies, and they returned to such traditional symbols as … the inevitable irish pig (iv), and this 12 january 26th issue of punch also characterised irish nationalist opposition to conscription with a repetition of its standard register of the demeaning irish stereotype at that time – as a ragged, filthy, uneducated, oppugnant, easily-duped peasant, a creature at home in the sty daring to address the affairs of state.

as noted by joseph p. finnan, many of punch magazine’s portrayals of the irish in the 1910s reflected persistent stereotypes of rowdy, unsophisticated peasants, symbolised by frequent representations of ‘paddy and his pig’. john redmond himself, a dignified member of the british parliament for nearly thirty years who looked as much at home in a top-hat as any british political leader, could not escape this stereotype. fully one-third of the portrayals of him for the period from 1910 to 1918 showed him in this ‘paddy’ identity, often with pig in tow. one cartoon even displayed redmond himself as a pig. (of course, this portrayal was not confined to the pages of punch, and in fact appeared frequently in many british publications of the time. depiction of redmond as a stereotypical ‘paddy’ complete with clay pipe, shillelagh and accompanying pig, surfaced in the daily graphic, the pall mall gazette, the westminster gazette and reynold’s newspaper.(v)

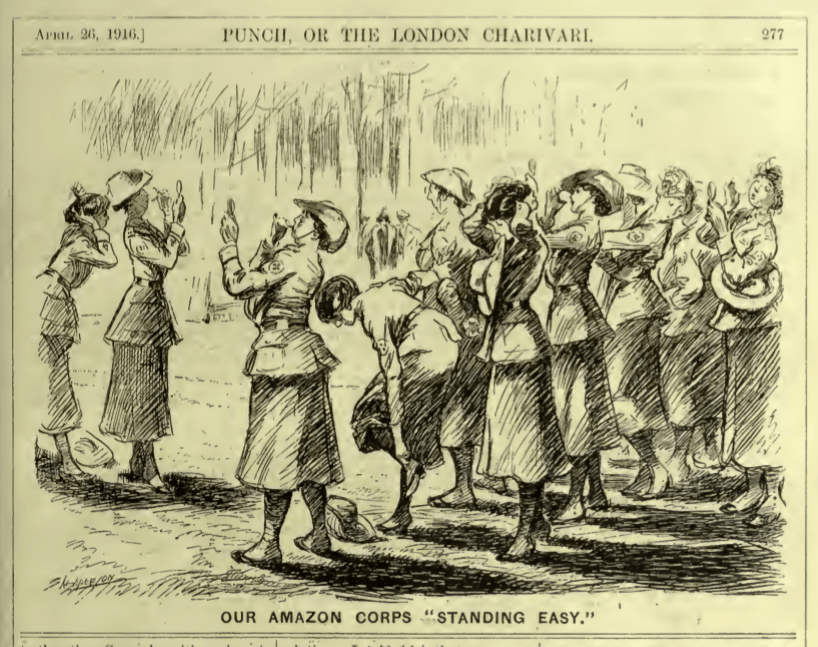

in the 26 april 1916 issue of punch magazine, the last issue published before the easter rising, the political affairs of ulster or ireland are featured only within the magazine’s regular parliamentary sketch column ‘essence of parliament’.

however, within this column the recent participation of ulster and irish mps in westminster is featured prominently, and within the language used there is a notable contrast between on the one hand, a condescending and patronising tone noting that mr (john) redmond’s irish nationalist party ‘followers’ regularly troop over from dublin to the rescue of a coalition parliamentary vote whenever needed, and on the other hand, a more reasoned note on the unionist (edward) carson’s participation that week within parliamentary debates at westminster, his call for full conscription to be introduced across ireland, in opposition to the call from nationalist irish campaigners for ireland to be exempted from the much debated new british policy of conscription.

one other point is worth noting here, indicating the discourse of punch magazine across this period . if this were the 26 april 1916 issue of the magazine punch being browsed through by miss annie baird, as she sits perhaps posed by the photographer william mckinley and as she is gazed upon, photographed and documented as she in turn considers the visual representation of punch magazine itself, then in this browsing miss annie baird will see through the magazine a telling visual commentary upon the new social function of women from the period, what is known as the ‘new woman’ of ww1, now being called upon and identified by government as agents of a new and now essential industrial, social, political and military function, as punch nevertheless continues to ridicule both (women in) their new jobs and the women who did nothing, but vacillated greatly between condoning female workers and deriding them…(and) found the changing role of women an easy target, but the fact that this subject was constantly employed for comedy throughout the war suggests that the paper was regrettably accurate in portraying themes the public found amusing. this is a very obvious way in which comedy was used to displace fear of change. … despite the changing demographics of britain during the war, patriarchal values still dominated the modes of cultural production. women were supposed to be unthreatening; they had little influence in the popular press and therefore punch was free to enforce more familiar attitudes of domesticity and male dominance. cartoons and articles satirising women dominated most issues. (vi)

notes:

(i) throwing a punch in ireland’s direction, patrick smyth, the irish times, april 25, 2012, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/throwing-a-punch-in-ireland-s-direction-1.508445, accessed 9/12/17

(ii) & (iii) punch’s portrayal of redmond, carson and the irish question, 1910-18 author(s): joseph p. finnan. source: irish historical studies, vol. 33, no. 132 (nov., 2003), pp. 424-451 published by: cambridge university press. stable url: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30006911 – accessed: 11-12-2017 12:39 utc

(iv) throwing a punch in ireland’s direction, patrick smyth, the irish times, april 25, 2012, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/throwing-a-punch-in-ireland-s-direction-1.508445, accessed 9/12/17

(v) apes and angels: the irishman in victorian caricature first published in 1971, l. perry curtis, quoted in joseph p. finnan above.

(vi) joseph p. finnan as above

(vi) esther maccallum-stewart, satirical magazines of the first world war: punch and the wipers times, http://www.firstworldwar.com/features/satirical.htm, accessed 10/12/17