genealogies and mappings

although the photographic practice of william fee mckinney did not begin until the 1880’s it does not stand apart from of his broader related interests across previous decades, with his photographic studies of kith and kin from the 1880s onwards being produced and assembled alongside his interests such as antiquarian studies, genealogy and local history and the collecting and display of artefacts. in fact across the five decades of mckinney’s life up to the 1880s, within the province of ulster and the whole island of ireland many rural populations had seemed to function on an ongoing basis as sites for typologies and discourses of display and observation, sites of interpellation within a society in which there was a complex interaction of identity formation, individual agency and culture: from the first 6′ mapping by the ordnance survey on the island in the 1830’s; to famine-related research visits across rural areas or farms from various commissions of enquiry from westminster or investigations into areas of ulster by charitable or aid institutions in the 1840’s and 1850’s; or across the 1860’s, 70’s and 80’s the pedagogic gaze of reforming landlords or politicians or reformers or authors; or the broader surveillance framework of the national network of notetakers of the royal irish constabulary and its network of paid petty informers delivering minutely detailed reports to the administration of dublin castle across the period of the land war; or the various graphic depictions from photographs of ‘eviction studies’ or urban sectarian riots for the national and international press of the time; and alongside these complex instances of visibilities, identities, opacities funcioning in ulster at the time, there were also other photographic studies of the region and its population being represented from the 1860s onwards within the essentialising paradigms of the picturesque and the antiquarian, such as the dioramas produced for events such as thomas charles stuart corry’s “diorama of ireland” active in belfast in the 1860’s or the those images being produced by ulster photographers for the lawrence collection of magic lantern slides and within groups such as the belfast naturalist field club.

the social practices listed above will ebb and flow across the development of this study of the contemporary rationale/demand for the production of the photographic practices of william mckinney and james glass, but here we will commence with the earliest of these – the first ordnance survey of the island in the 1830’s covering the period of mckinney’s childhood in sentry hill:

in 1824, a house of commons committee recommended a townland survey of ireland with maps at the scale of 6″, to facilitate a uniform valuation for local taxation. … the survey was directed by colonel thomas colby… civil assistants were recruited to help with sketching, drawing and engraving of maps, and eventually, in the 1830’s, the writing of the memoirs (from the ordnance survey memoirs of ireland, volume two, parishes of county antrim (i), 1838-9, ballymartin, ballyrobert, ballywalter, carnmoney, mallusk, pub the institute of irish studies, belfast & the royal irish academy, dublin, 1990)

this usefully establishes two things – firstly that within mckinney’s childhood years, a significant survey was conducted, making an official recording, as map and hand drawn sketches and written accounts of this community, as part of the massive national undertaking of the first ordnance survey mapping across the island of ireland. this process was of such significant scale that it was both a national event and an event which made a significant presence within each local rural population, with by the late 1830’s a total of no less than 2,139 ordnance surveyors ‘crawling over the face of ireland’ (i) in a what was described in its time as ‘an embrace of anthropology, statistics, toponymy, antiquarianism, geology and map making … held up to be an exemplary model of interdisciplinarity’ (ii) and described since as a late exemplar of the enlightenment’s enthusiasm for ‘a vibrant public sphere of fevered collaborative discussion’ (iii).

on the ground, so to speak, within communities such as the parish of carmoney and the townlands of ballyvesey, ballycraigy, ballyhenry and mollusk that surround sentry hill, this event would have been experienced as follows:

landowners and professionals (who) were members of antiquarian or literary societies, amateur collectors, and authors of local studies … introduced ordnance survey staff to other antiquarians, showed them the antiquities of the region, and allowed them to use their private museums and libraries, which often held valuable artifacts and manuscripts…. proprietors who held legal or political office, land agents, bailiffs, tithe and cess collectors supplied the ordnance survey with voluminous records and shared their expert knowledge… clerics, schoolmasters, small farmers and labourers, were excellent sources of information, especially in the countryside where there was continuity of settlement, and in Irish-speaking or recently anglicised areas where oral culture was still strong…. in rural ireland, generations of families often lived in the same place and preserved traditions about local place-names, history and legends, which they imparted to ordnance survey staff. topographical department scholars sought out teachers and clerics in particular, who often traveled with them to procure information, pointed out historic and archaeological sites, introduced them directly to ‘qualified inhabitants’, and put them in contact with knowledgeable people elsewhere…. most people gave assistance freely and generously… (iv)

in fact, we can speculate with some certainty that within william fee mckinney’s childhood years that part of the mckinney family itself may have had the experience of a direct conversation with the note-takers and researchers of the ordnance survey. we can with some confidence assume a mistake in the written account of a ‘mckenney’ being consulted in the carnmoney parish as part of the survey, and we can assume the true name was mckinney as no mckenneys appear in records of carnmoney in this period. and so the we have a view from the ground provided by this survey:

extracts from fair sheets by thomas fagan, february to april 1839: ancient topography: discoveries in carnmoney: in carnmoney and holding of miss mckenney, and about a quarter of a mile north west of the church were discovered beneath the surface within the last ten years, quantities of decayed human bones, also a small earthen urn containing calcined bones and ashes…. the tract of ground in question was an ancient graveyard attached to the ancient city of cool, said to have stood in this district … it is further added that in the aforesaid miss mckenney’s farm stood an old draw-well which is now closed, but in which is deposited a large quantity of gold, silver and other valuables belonging to the above ancient city, and which was conveyed to it in carloads at a period when the city was threatened with destruction. (99)

and regardless of any direct contact, the process of the ordnance survey surrounded each and every homeplace. see for example the illustration above this blog posting features the part of the mapping process known as the detail survey with theodolites and chain lines, in which:

district commanders then used smaller theodolites to observe the secondary and tertiary trigonometric network. chain lines were run between the tertiary stations giving a check on the trigonometrical computed distance and facilitating the subdivision of the triangle for detail chain survey every road and track. all and hedge, river and stream, house and barn was surveyed and mapped. (v)

beyond the physical survey of the land, and beyond conversations and interviews recording the oral accounts of local antiquarian legend, the work of the written ordnance survey memoirs of ireland was experienced on the ground as research enquiring into into the broader dynamics and relations within local society, with queries into everything from manners to commerce and society:

extracts from parish of carnmoney, county antrim, memoir by james boyle, 28th april 1839:

ballycraigy, ballycraig: ” the townland of the rocks”, from bally and craig “a rock”. there are several little basaltic hummocks or cliffs in this townland…

ballyesey, “the town of the vesesys”… (34)

gentlemen’s seats: there are in this parish 17 gentlemen’s residencies, which with 2 exceptions are situated along its coast and which are nearly all of comparatively modern erection… they are with a few exceptions the property of a wealthy mercantile aristocracy, most of their owners being still engaged in trade as belfast merchants and a few of them having within a few years retired to the country… (46)

it is interesting to consider this discourse of status within a small social setting of this parish as the social and cultural framework within which william mckinney was born and raised, and within which he then in his subsequent adult years achieved a not insignificant economic status of a gentleman farmer of some 100 acres. we could speculate that with the fact that the peak of the social status within this parish at the time being a wealthy mercantile aristocracy – in contrast for example to the arguable illegible ahistorical lineage and attendant status (fetish?) of a landed aristocracy – such a tradition of a local elite would be comfortably within the reach and within the field of vision of a gentleman farmer of some 100 acres, such as william fee mckinney.

the photograph above has been described elsewhere as:

during the early years of the new century parties were often held at sentry hill. the photograph was taken by william mckinney on one such occasion in June 1902. present were all members of all the leading carnmoney families. (my emphasis) they included substantial farming families such as the chisolms and the houstons and also those like the mcbrides, wilsons, and boyds who owned local industries. (78) (vi)

both this photographic portrait and this act of photographic portraiture function within what has been described as the informal socialization of elite groups (vii), determining mckinney as kith and kin within the wealth and status, within the social, political and cultural capital of a mercantile aristocracy, and in fact determining a mercantile aristocracy as a legible narrative against which a gentleman farmer of some 100 acres – and furthermore a gentleman farmer situated upon the foundation of a thoroughly researched and documented lineage of a place within the parish – could measure and determine with some satisfaction his own social, political and cultural capital.

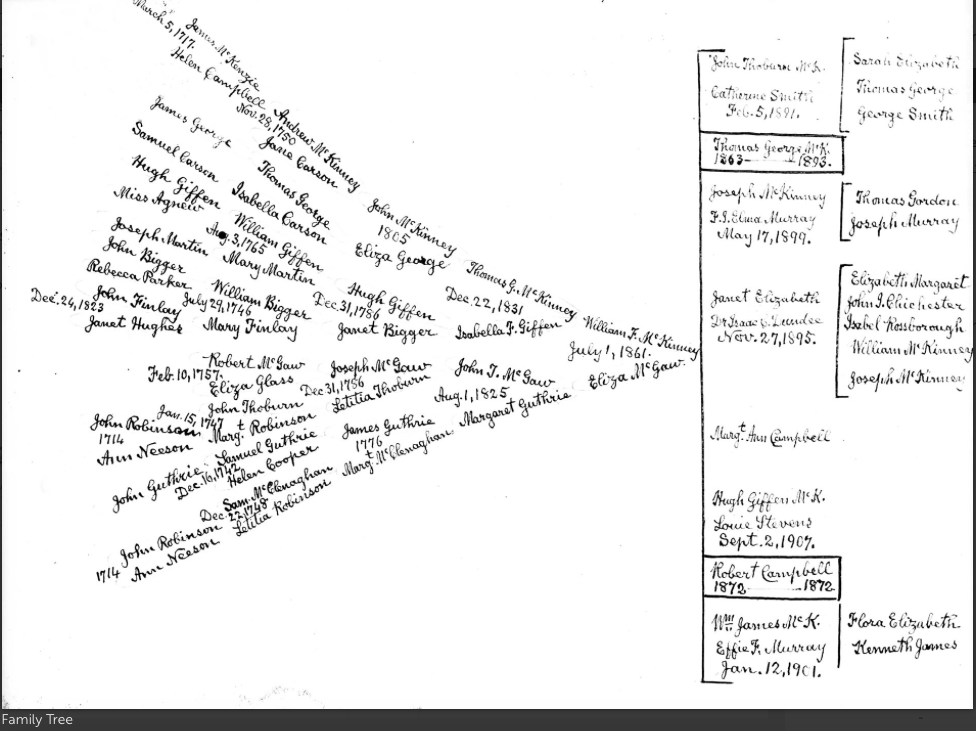

(image above is the mckinney family tree, researched, documented and handwritten by william mckinney) (marx on genealogy, heraldry, zoology may be of use here with reference to mckinney’s antiquarianism.)

and while this parish of carnmoney in which a gentleman farmer of some 100 acres resides could not in any sense be considered a nationally or regionally significant location, it is important to note that these accounts record that it is not remote, and that within it there are communications facilitating contact with the regional centre of infrastructural power, finance, innovation, culture:

extract from: parish of carnmoney, county antrim, memoir by james boyle, 28th april 1839: communications,: roads: few districts are so amply provided as this, there being 13 miles 4 furlongs 34 perches of main and 19 miles 4 furlongs 16 perches of by and cross-roads, including the old main roads which have been superseded by the improved lines of modern construction. the roads are in fact much too numerous, but this arises from the number of important leading lines which traverse the parish and from there necessary improvements upon the old ones by the construction of those more suited to the great traffic between belfast and the districts west and north of this parish. all the leading roads from the northern and western portions of this county, and from the county derry and northern part of tyrone to belfast, pass through this parish, and all the present main roads have been constructed within the last 8 years, and their number thereby been doubled. (49)

(i) (ii) and (iii) rachel hewitt, map of a nation: a biography of the ordnance survey, london granta, 2011

(iv) gillian smith, an éye on the survey, history ireland, issue 2, summer 2001, volume 9, 2001

(v) https://www.osi.ie/about/history/interior-survey/

(vi) Brian M. Walker, Sentry Hill: An Ulster Farm and Family, Dundonald, Blackstaff, 2001

(vii) one of the most important considerations in historical sociology has been the question of social capital, social status and the informal socialization of elite groups. this is a feature of the work of bourdieu… (25) in ciarain o’nell, ed. irish elites in the nineteenth century, dublin, four courts press, 2013

(featured image above this posting is ‘royal sappers and miners at work’ from gillian smith, an éye on the survey, history ireland, issue 2, summer 2001, volume 9, 2001)