The animal was widely referred to as ‘the gentleman who pays the rent’, because he was fattened all year to be sold at market, and the proceeds of the sale traditionally provided rent money. (Claudia Kinmonth, Irish rural interiors in art. New Haven and. London: Yale University Press, 2006, p111)

As in the previous posting, here again, in deciding in this instance to curate the photograph albums of William Fee McKinney as folklore, we can read the photographs of McKinney against the grain, that is against the legend which McKinney provides as the only description accompanying these photographs – Tom Couley, Pig Killer, c.1895.

Whilst reserving the strategy of also interrogating these particular images as part of McKinney’s apparent typology of rural workers, we can here also indicate in McKinney’s Tom Couley, Pig Killer, c.1895 photographs a subaltern counter memory, we can indicate a performance and a trace of a concurrent stereotype seized upon by critics of Irish society, who liked to lampoon ‘the pig in the parlour’ and the position of the featured animal, as opposed to the featured human subject Tom Couley, as a central figure of the age, ‘the gentleman who pays the rent’.

In the poor rural nineteenth-century home, the pig lived indoors, on the same boiled potatoes, as the rest of the family … By the nineteenth-century the pig as a ubiquitous addition to most rural households was commented on by virtually every traveller to Ireland. The more perceptive writers recognised that it was just the most fortunate farmers who kept a pig: Gustave de Beaumont observed in 1839:

From Gustave de Beaumont, Ireland: Social, Political, and Religious, vol. 1 [1839]: “The physical aspect of the country produces impressions not less saddening. Whilst the feudal castle, after seven centuries, shows itself more rich and brilliant than at its birth, you see here and there wretched habitations mouldering into ruin, destined never to rise again. The number of ruins encountered in travelling through Ireland is perfectly astounding. I speak not of the picturesque [266]ruins produced by the lapse of ages, whose hoary antiquity adorns a country—such ruins still belong to rich Ireland, and are preserved with care as memorials of pride and monuments of antiquity—but I mean the premature ruins produced by misfortune, the wretched cabins abandoned by the miserable tenants, witnessing only to obscure misery, and generally exciting little interest or attention.

But I do not know which is the more sad to see—the abandoned dwelling, or that actually inhabited by the poor Irishman. Imagine four walls of dried mud, which the rain, as it falls, easily restores to its primitive condition; having for its roof a little straw or some sods, for its chimney a hole cut in the roof, or very frequently the door, through which alone the smoke finds an issue. One single apartment contains the father, mother, children, and sometimes a grandfather or grandmother; there is no furniture in this wretched hovel; a single bed of hay or straw serves for the entire family. Five or six half-naked children may be seen crouched near a miserable fire, the ashes of which cover a few potatoes, the sole nourishment of the family. In the midst of all lies a dirty pig, the only thriving inhabitant of the place, for he lives in filth. The presence of the pig in an Irish hovel may at [267] first seem an indication of misery; on the contrary, it is a sign of comparative comfort. Indigence is still more extreme in the hovel where no pig is to be found.” [Gustave de Beaumont, Ireland: Social, Political, and Religious, vol. 1 [1839]]

The animal was widely referred to as ‘the gentleman who pays the rent’, because he was fattened all year to be sold at market, and the proceeds of the sale traditionally provided rent money.

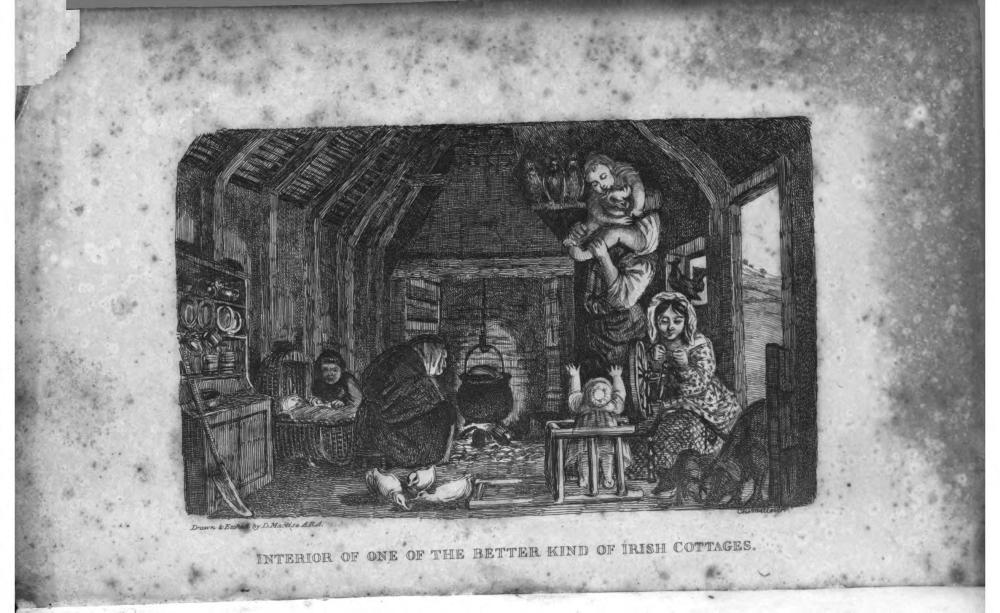

Interior of one of the better kind of Irish cottages, Daniel Maclise, 1836

… illustrations bear witness to the pig as a common occupant of the kitchen. Maclise shows him wandering through the open door … Although his presence was a stereotype seized upon by critics of Irish society, who liked to lampoon ‘the pig in the parlour’. Maclise had no such hidden agenda, and was undoubtably relating what he was familiar with.

(Claudia Kinmonth, Irish rural interiors in art. New Haven and. London: Yale University Press, 2006, p111/112)