principles and elisions

we outlined in our previous postings the argument that we can identify within the photographic practices of both william fee mckinney and james glass the fierce sense of place, home, family that was situated within the irish popular mentality (i) of the late 19th/early 20th century. but we should not delimit our exploration within these two photographic practices to solely those discourses active only within the island of ireland and commonly related to nationalism / republicanism / sectarianism, or religious or contested national identity. within the body of these photographic practices, there will be displayed the traces of discourses that reach beyond these boundaries, that engage with ideas and events with transnational influence. historian nini rodgers has noted that

it was the revolutions in america and france that encouraged the political activities and ambitions of the ulster presbyterians … (with the revolution in France) … leading the world toward liberty, equality and fraternity, signifying the end to autocracy and the domination of aristocracy and priesthood. (ii)

for the period of this influence, the presbyterian community around sentry hill and carnmoney and the county of antrim was not in any way remote or distant from the influence of such ideas. it was in fact only some few miles from the centre of events and debate. as an example, the society of united irishmen, who sought to plant these reforming and revolutionary ideas in ireland, was formed by radical ulster presbyterians in nearby belfast in october 1791. the society sought the end of perceived injustices in social and legal conditions in ireland, among them the submission to a church of ireland aristocracy and any demand for tithes to such institutions – such as the tithe demanded by the local church of ireland aristocracy from the mckinney’s own farm.

as evidence of the reach of such radical ideas within the mckinney family, there is an artefact featured within a photograph by william fee mckinney, and still physically present within the mckinney collection of family artefacts/heirlooms, which marks and celebrates late 18th century revolutionary events and radical political discourse across europe – the commemorative jug featured above, which celebrated the fall of the bastille in 1789, and which was presented to william’s grandfather’s brother james mckinney in county antrim in the 1790s.

and further, william mckinney’s own writings reflect upon how both his grandparents

joined the united irishmen who at first united only on reforms being made in the existing government without any intention of fighting…. (iii)

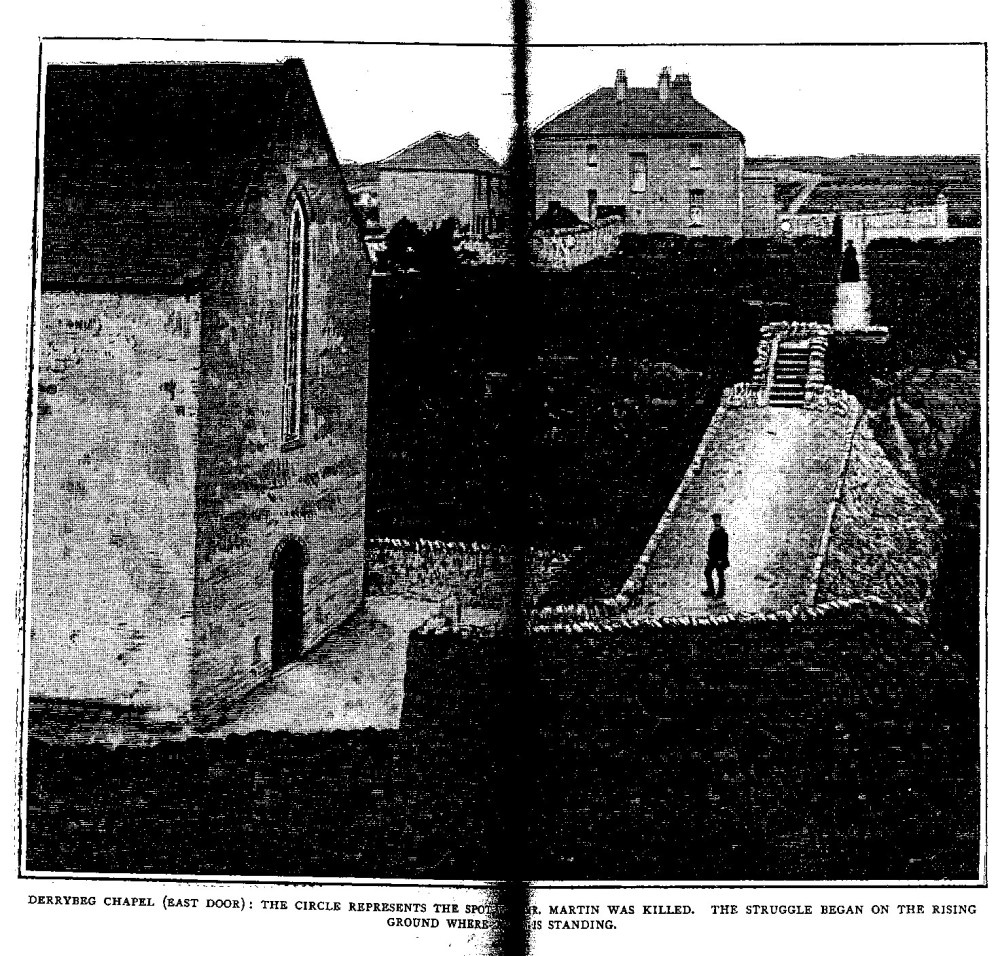

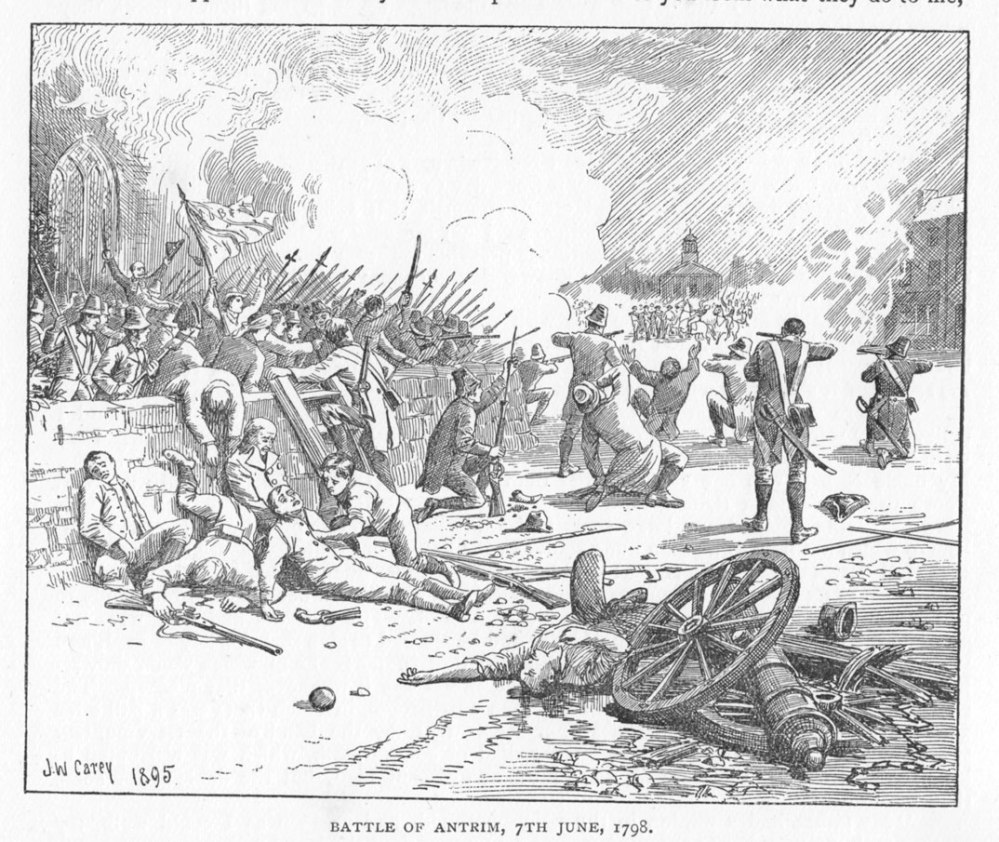

and after suppression and the execution of members of the society of united irishmen, preparations for their 1798 rebellion were commenced. and in the rebellion itself, in june 1798 mckinney’s grandfather carried the signal for local united irishmen to rise and march on antrim town – but the rebellion failed. william’s great-uncle, samuel george, was killed at the battle of antrim, an event that was still being commemorated visually within the period of mckinley’s own adult years by respectable figures such as the artist reverend jw carey of county down, who in 1899, set up a business in belfast (carey & thomson) specializing in high quality illuminated addresses, presentation albums, and book plates ( and we can speculate and research further any connection between carey’s business as a source for mckinney’s own albums).

there is a perspective which could propose that the primary reading of william fee mckinney’s adult years should recognise no role or influence of such radical ideas, as any engagement with radical causes within his familial or social milieu simply ceased after the 1798 rebellion. for example, it is recorded that in 1800 mckinley’s grandfather john mckinney, as a freehold voter, had signed a petition in favour of the act of union between england and ireland. (iv)

however, the defeat of the united irishmen

did not mean the end of their ideals, and dr william drennan, coiner of the principles of the united irishmen, was a founder in 1810 of the belfast academical institution, among whose aims was demonstrably the continuation of revolution by other, educational, means as articulated in drennan’s wish that: ‘ a new turn might be given to the national character and habits’ … (v)

and its is therefore noteworthy that subsequently, for three generations, the mckinneys selected this belfast academical institution as the primary educational influence upon most of the young sons within the mckinney family, with two of william fee mckinney’s brothers and all of his own sons and several of his grandsons being taught there. of course across a century from the late 1790s onwards, the urgency and visual primacy of such radicalism did diminish but it could be argued – despite the fact that in 1831 the school the belfast academical institution accepted the title of ‘royal’ preferred by king william iv (as the institute itself argues, this was a process engaged in less out of loyalty, than the need to appropriately distance the institution, in the later nineteenth century, from its radical-republican origins and to secure a government grant to maintain the collegiate department (vi) ) – that the role of the royal belfast academical institution within the family lineage of the mckinneys, through the shared relation within the lineage of the school and the mckinneys to 1798, the united irishmen and allied radical, reformist and revolutionary ideas, functions at least as trace of this radical lineage.

so can the strands of the radical, reformist and revolutionary perhaps be traced within the photographic practice of william fee mckinney himself? we can speculate for now that the photographs by william fee mckinney below, of his grandchildren thomas mckinney and jack dundee, may feature a belfast academical school uniform or at least a belfast academical school cap :

from such traces being identified and made visible in the photographic practice of william fee mckinney, we have been able to indicate the progressive elision of the radical, reformist and revolutionary from the presbyterian community within which the mckinneys of sentry hill worked and lived. as the united irishmen had the radical aim of uniting ‘protestant, catholic and dissenter’ we can perhaps characterise this as the regressive elision of dissent from the dissenter. but we can, through a process of indicating signs of this lineage where they are displayed within the photographic practice of william fee mckinley, develop an argument against this visual elision.

furthermore, we can can expand this argument beyond the specificities of the framework solely of ulster and ireland.

for the mckinney’s, the period of their relationship to sentry hill across the 1790s to the 1880s commenced with john mckinney (william mckinney’s grandfather) acquiring a 31 year lease on a 20 acre property – and with both of william fee mckinney’s grandfathers being engaged with the radicalism, rebellion and reform, the french revolutionary ideals of liberty, legality, fraternity, and the united irishmen. and the period ended with william fee mckinney having by the 1880’s full (non-leasehold) ownership of almost 100 acres, and with him acting as a minor landlord of farming land and of built property, so accumulating financial capital allied to an accumulation of social and cultural capital, such as a developing influence for william within the respectable bodies and institutions of his local community around sentry hill and developing affiliations with respected belfast societies etc.

so we can outline a gradual process across this period within which any agency as radical or dissenter was being eclipsed by agency as a secure part of the bourgeoisie.

the historian marc mulholland’s bourgeois liberty and the politics of fear can be used to indicate a key perspectives on reading such a process, by letting us survey the developing ‘radical to bourgeois’ status of the mckinneys at sentry hill through the broader perspective of european history and class history. initially quoting jurgen kocka, outlining that within the development of the bourgeoisie across this late 18th to late 19th century period, the parallels with the development of the mckinneys at sentry hill are striking:

in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they (the bourgeoisie) set themselves apart from the world of aristocratic privilege, unrestricted absolutism, and religious orthodoxy;

– within this argument we could situate the mckinney’s allegiance to radicalism, rebellion and reform, the french revolutionary ideals of liberty, legality, fraternity, and the united irishmen and participation in rebellion –

and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries… ( they (the bourgeoisie) set themselves apart) … from those below them, the lower strata, the people, the working class… the different sections of the bourgeoisie shared a common culture, defined by a specific type of family life and unequal gender relations, respect for work and education, and emphasis on personal autonomy, achievement and success; and by a specific view of the world and a typical style of life in which clubs, associations, and urban communication played an important role. (vii)

mulholland’s analysis continues to almost mirror this latter social framework of the mckinneys of sentry hill as displayed within the photographic practice of william mckinney:

the point about bourgeois civil society, with its foundation of association, family, education, and assets of inherited property and wealth, is that it prepares its members to actualise their marker potential not just through formal education, but also childhood socialisation into habits of self-confidence, communication skills, and attunement with the dominant culture of success. bourgeois ‘habitus’, as pierre bourdieu put it, generates valuable ‘social capital’ and ‘cultural capital’, which in turn leverages ‘real’ capital… (viii)

(i) kevin whelan, eviction, in ed. wj mccormack , the blackwell companion to modern irish literature, oxford, 1999 quoted in l. perry curtis, the depiction of eviction in ireland 1845-1910, dublin, ucd press, 2011, p24

(ii) nini rodgers, “transatlantic family journeys”, in faith and slavery in the presbyterian diaspora, ed. william harrison taylor, peter c. messer, rowman & little field, 1988

(iii) william fee mckinney quoted in brian walker, sentry hill: an ulster farm and family, dundonald, blackstaff, 2001

(iv) http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/sBUMrosHRsqp6HkinzkVCA

(v) david cairns & shaun richards, writing ireland: colonialism, nationalism, and culture, manchester, manchester university press, 1988, p22

(vi) http://www.rbai.org.uk/index.phpoption=com_content&view=article&id=3&Itemid=362

(vii) marc mulholland, bourgeois liberty and the politics of fear: from absolutism to neoconservatism, oxford, oxford university press, 2012, p4

(viii) marc mulholland, bourgeois liberty and the politics of fear: from absolutism to neoconservatism, oxford, oxford university press, 2012, p7

![L 440-2[1].](https://theempireofthesenses.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/l-440-21.jpg?w=1000)