theatre

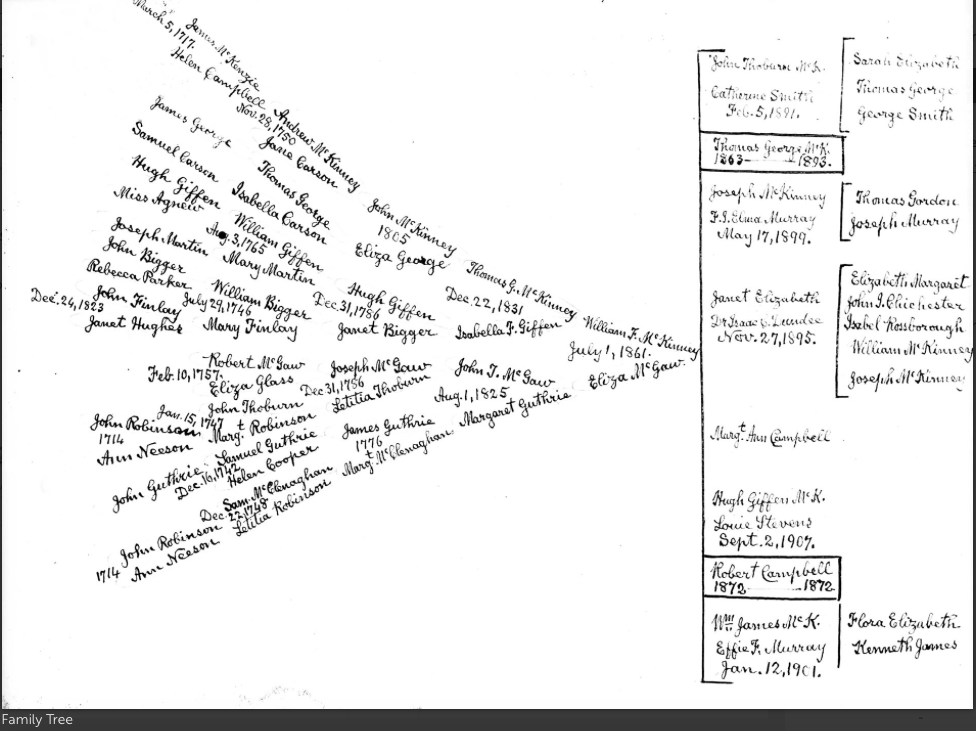

One of the reasons that the definitive interpretation of the McKinney photograph albums may seem problematic is that the albums have a kind of oscillation as their character or at their core. There does seem to be one an overarching framework for the albums, that of the domestic, which is communicated in the readings provided by substantial texts on the collections such as that of Walker and the reading provided by the institutions circulating the collection, that is NMNI, the Sentry Hill Museum and PRONI. And yet we can indicate traces prompting multiple possible readings of agency made apparent across the albums – for example as a typology or as a document or as a series of still lifes. To interrogate this, three arguments are necessary here: the domestic in photography itself; what has been termed as the surface and how what has been termed as the ‘dense context’ (Edwards, see below) both function within photography; and the traces prompting multiple possible readings of agency made apparent across the archive albums – for example as a typology or as a document or as a series of still lifes.

There are the surface readings and surface level assurances regarding any domestic family album circulated in the descriptions and textual exegesis of McKinney’s photographs from his albums in websites, catalogue entries and books provided by NMNI, PRONI and Walker. The problematic of this framework of readings being circulated and communicated is best interrogated by Edwards when she outlines how the context of a photographic object is often articulated as a closure of meaning for it, how the description of “the who, what, why and where of the making of the photograph and the portrayal of its content” (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p262) results in a closure of meaning. In my earlier posts I have referred to an ‘originary agency’ for a photograph album as only one of several possible modes of agency apparent in and through any archival photographic object, and Edwards refers to how a closure of meaning is sometimes derived from this “ ‘functional’ or ‘originating’ context … that this is the context that defines the creation and existence of the photograph, anchoring it as a functional document/object.” (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p262)

Both Edwards and others argue that in exploring the domestic family album, both the visibility of presence and the erasure of absence are central in constructing meaning. One of the questions that these that we must return to often is “what does ‘being in the album mean, and, conversely, what does not being there mean” (Richards Chalfen, Snapshot versions of life, p11) Crucially, Edwards expands on this meaning of the absent to outline the function of what she terms as the “dense context”. The “not necessarily apparent” (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p263) of what the photograph is of communicated as an integral part of the layering of meaning in an event and a representation, the function for what is absent within an event and its representation within the construction and circulation of its meaning.

Although Chalfen’s interrogation of photograph albums focusses upon late twentieth century ‘snapshot’ culture, his commentary can still engage as a provocation within a reading of an archival photographic collection. Where Chalfen notes the ubiquity of participation within his contemporary society of the practice of domestic photography, ‘Cameraless people often become part of other’s home photography (and are given pictures of themselves). They can also have personal pictures made in … inexpensive studio settings” (Richard Chalfen,Snapshot versions of life, p.15) this comment can also serve to indicate a power dynamic seemingly obscured by its overt visibility – that relationship between the photographer and the subject, in our case here, the decision made by the photographer McKinney to document his subject. Where and with whom, is the agency in this practice? What is the power relationship? Are there signs that mean it can it be read as an negotiation, collaboration or exchange or an imposition, demand or coercion of unequal relationships? What can be indicated if we follow Edwards when she writes of specifically “thinking through” nineteenth-century photographs to indicate and interrogate the “nineteenth-century performance of space, identity and power”, thinking beyond the “forensic content of the images themselves”. (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p261). Some examples here from the McKinney albums are the several photographs of tradesmen at work within the grounds of McKinney’s Sentry Hill homeplace. Two of these phototographs and their description feature the selected subjects both at rest and active at work specifying an intent to include the act of work within this image (and perhaps even this could be termed as within this series, and the potential to discuss these photographs as a series and a typology will be explored later) and here it is enough to indicate that there is some transactional relationship within the act of photography – the power of a commercial exchange from payer to payee.

There are other photographs that feature the practice of work and workers at Sentry Hill. However for these above what we need to indicate is that although, as Edwards comments, “power itself is too crude an instrument for measuring all the subtleties that make up the interaction within (these) photographs, for just as many meanings coexist in one photographic image, so many spaces coexist in one physical space” (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p276), power is one of the relationships that is communicated in these photographs, and we can indicate this power relationship of a commercial exchange as part of the ‘originary agency’ or ‘functional’ or ‘originating’ context in these photographs. In this domestic homeplace the photographer, landowner, landlord has superior social and economic capital than these manual workers.

We know also that Caldwell, the labourer, also featured in one of these photographs, was in fact also a tenant at Sentry Hill and like several of the McKinney’s tenants at Sentry Hill could partially pay for his rent through such work at the farm for McKinney. (Walker, Sentry Hill, p115)

These photographs do not feature commercial relationships or the power of a commercial exchange from payer to payee in which the photographer is in an equal of inferior position, such as making payment to a representative of the state or negotiating with a bank manager or a member of the medical profession.

This choice in displaying one form of commercial relation, one set of social relations and social status, in these photographs can further indicate agency for the Sentry Hill albums of photographs if we follow Chalfen who asks “What do ordinary people do with their personal pictures, and in turn, what does this imagery ‘do for’ ordinary people. … Any study of communication must attend to human involvement in both sides of the message form – production of the message and reception of the message … as encoding and decoding … how ordinary people interpret or reconstruct the rendition of life that is repeatedly presented in home industry” (Richard Chalfen, Snapshot versions of life, p119) These photographs, their polysemous meaning anchored by written explanation identifying the subject by name and profession, sit in the photograph collection of a relatively wealthy family farm, made by the Victorian master of the homeplace – the father and husband. These photographs – within their polysemy of their function – reinforce this status.

We particularly note here that that there are two photographs of Couley, the pig killer and two photographs of Wells, the tailor. In each case, one photograph features the subject posed simply standing or sitting, the other features the subject posed at work, acting out their profession for the camera. We can read in this doubling of the event of photographic portraiture the function of performativity within this series of images. It indicates that it is insufficient for the originary agency or the functional or ‘originating’ context for this act of photography, to have a portrait photograph that features the subject. The originary agency or the functional or ‘originating’ context for this act of photography is a scene of the subject as worker, at work within the domestic homeplace of the photographer. There is a convergence of the domestic space and the social function, the social status, and social relations displayed in the image of the working subject at work within the domestic space, and consequently within the display of these photographs in the domestic space there is a framework of social or power relations staged – a term chosen deliberately here. That staging within these acts of photography made and presented in the photographer’s domestic space follows further argument from Edwards. In her discussion of photography, space and power within a nineteenth-century archival photography collection, Edwards uses the term theatre for how her selected archival photographic images are constructed. Edwards’s specific meaning for that term theatre in this context is most significant here: “a representation, heightening, containment and projection, a presentation which constitutes a performative or persuasive act directed towards a conscious beholder.” (Edwards, Negotiating Spaces, p262). This specific sense of performativity and theatre can be indicated elsewhere with McKinney himself as subject, in an ambrotype of McKinney during his years in the 1860s in Canada, posed in the photographer’s studio complete with axe as prop as a woodsman, with a painted backdrop behind him.

If McKinney’s own photographs some years later of workers posed with their tools of labour in his own homeplace of Sentry Hill can act as an echo or carry the resonance of such performativity within photographic portraiture, then there is a similar resonance that we can indicate within the domestic space constructed within the photography albums of McKinney. And this in turn brackets this practice to the representations of the domestic and filial constructed within the studio practice of James Glass.

References:

Richard Chalfen, Snapshot versions of life, Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1987

Elizabeth Edwards, Negotiating spaces: some photographic incidents in the Western pacific, 1883–84 in editors Ryan, James R & Schwartz Joan M, Picturing place: photography and the geographical imagination, Tauris, 2003

Brian Mercer Walker, Sentry Hill: an Ulster farm and family, Dundonald: Blackstaff, c1981

![L 440-2[1].](https://theempireofthesenses.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/l-440-21.jpg?w=1000)